How to Teach VC With a Board Game

In this post I share details on which VC concepts are taught through playing Swagger.

After a year of testing, I can confidently say that I've found a better way to teach venture capital using a board game.

In this post I'm going to share details on what that looks like and highlight which VC concepts are taught through gameplay.

The game is Swagger and I started developing it over a year ago.

Since then I've used it in founder workshops and tech events including Startupfest recently. I end each game session with a discussion and this is where I sit back and observe what's been learned.

I hear founders talking about dry powder, unreasonably high valuations, their fund thesis and the lack of liquidity.

This is after playing only once.

Why games are good teaching tools

Games are a sneaky way to teach. The desire to win motivates players to learn the rules of the game and try to find the optimal strategies. It's only later players discover they've internalized business concepts.

In Swagger, founders step into the shoes of a VC and manage their own fund, competing for the highest returns. Dealing with the challenges of running a fund is exactly the shift in perspective that allows founders to understand funders.

A game can be replayed to test out new strategies or simulate different scenarios. Eg. the game includes industry-wide fluctuations that can be used to see what happens when industries go up or down.

Finally, the game is competitive and players can behave unpredictably. This is incredibly entertaining but also captures the human element of investing in startups. Reading about volatility is one thing. Having someone chase you around the room with the Cramdown card is another.

I'm not going to describe in detail how to play Swagger because it's not necessary for this post. But read this if you're interested.

VC Concept: Time

Time is obviously central to the VC model. A fund has a fixed lifespan, usually 10 years. That puts a limit on how much time is left to generate exits and liquidity. In turn, that means VCs need to do the bulk of their deals in the early years (or they run out of time).

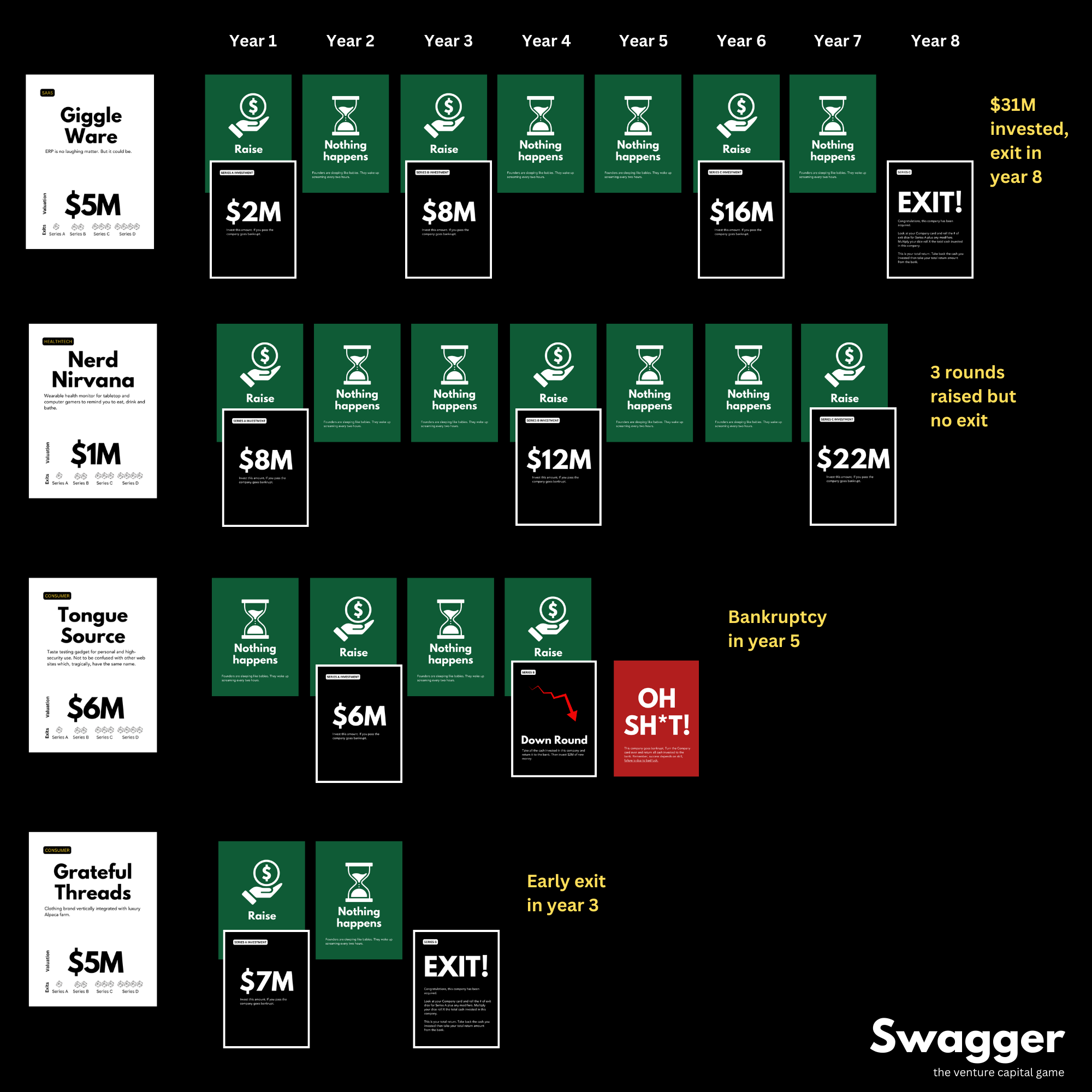

There are a lot of ways to read about the element of time in closed-end funds. Swagger makes it visual as you can see from this snapshot of a VC portfolio over 8 years:

In the game, a player turns over cards every turn/year to reveal what happens, eg. raising a Series A. Each person manages their own portfolio, but you could also use the cards solitaire-style to quickly see what can happen to a portfolio over the life of the fund.

The image above shows 4 very different outcomes:

- Ideal - Series A, B and C followed by an exit in year 8. This is an ideal case as it returns funds to LPs before the end of the fund.

- Unrealized Potential - A slightly slower growth path that still leads to 3 funding rounds but no exit and no liquidity (at least in Fund I).

- Failure - The company fails in year 5. Companies fail regularly in Swagger.vc at the exact same statistical rate as real life (unfortunately).

- Early Exit - This generates a small but profitable return which is not attractive for the fund manager.

There are an infinite number of possibilities using the different cards in the game. I'm already thinking about expansion packs.

From a teaching perspective, the element of time is captured by having only 8 turns to win the game. As the game progresses, players feel the pressure to find exits. Most founders still do not understand that venture capital funds speed.

Time also forces difficult player decisions. As the years tick down, and dry powder runs out, players will have to decide which companies to support. They'll have to ask themselves which companies are likely to have the biggest exits within the fund's timeframe.

This is a difficult perspective to teach but happens automatically in the game.

I've discovered that founders are ruthless when it comes to killing companies when they need to!

VC Concept: Power Law & Uncertainty

The Power Law is a simple concept that still manages to make VCs seem smart when they write about it.

20% of the portfolio will generate 80% of the total fund returns.

Or one or two hits will generate all the returns.

The problem is no one can tell which startups will become hits.

In Swagger most events that happen to each portfolio company are random. Whether a company is fundraising, or goes bankrupt or is affected by industry-wide events is outside the player's control. This models the uncertainty built into VC (but can feel uncomfortable to a gamer who wants more control).

Here is an example of 4 different paths a company can take in Swagger based on the randomness of the cards:

You can change the distribution of the cards to increase or decrease difficulty. Eg. there could be more Raise cards to simulate a frothy market, or more Oh Sh*t cards to represent a downturn.

Either way the game is designed to force players to ask themselves: what is Power Law seeking behavior?

It's possible to play it safe in Swagger.vc, ensuring the maximum number of companies survive to the end. This ensures you don't lose the game but also ensures you'll rarely win. A riskier VC portfolio will almost always generate a higher return than a conservative one.

VC Concept: Power Law & Big Markets

Not being in direct control of how the portfolio companies perform also reveals another principal of the Power Law:

Even if you don't know which companies will take off, there'd better be a huge market if they do.

Built into Swagger is the concept that small returns, eg that you would get in an early exit, are only useful if they give you dry powder that you can deploy before the end of the game.

Otherwise, every single startup needs to have the potential for a big exit because no one knows which one will take off (except the founders, 100% of whom know they are the ones who will succeed).

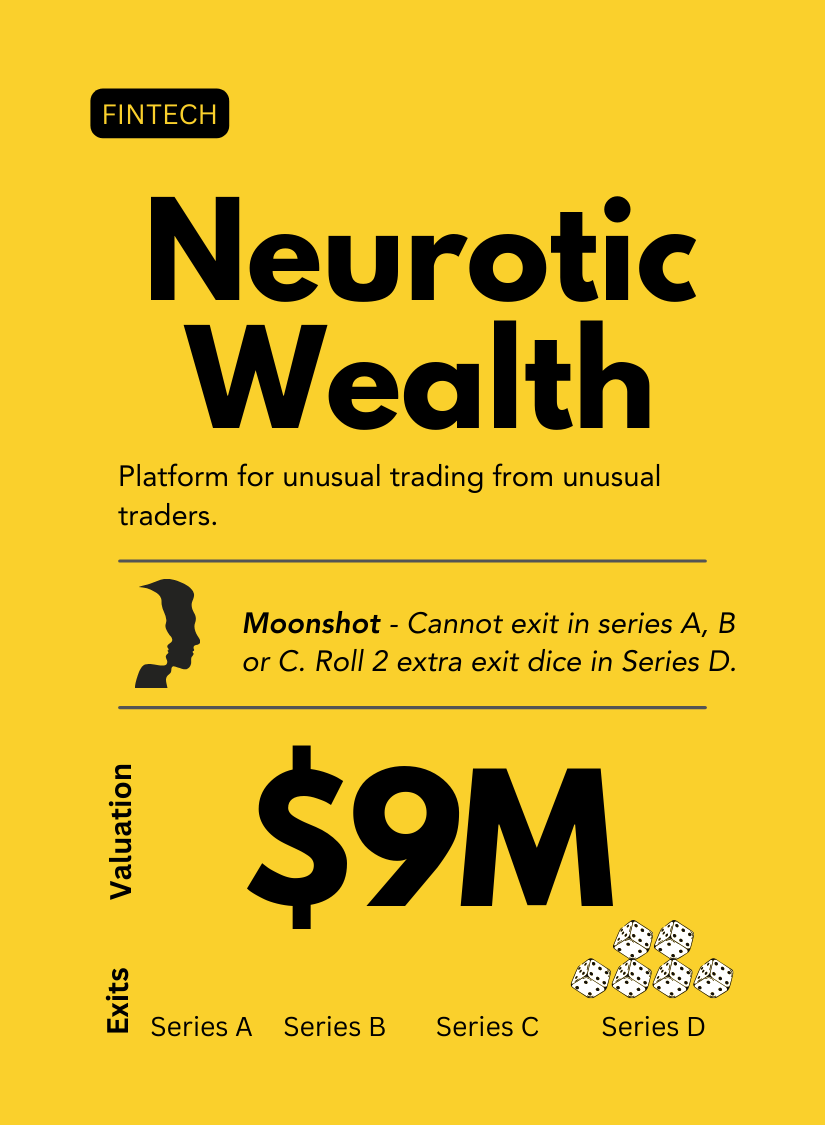

"Neurotic Wealth" (not a real company, yet) is an example of one of the highest risk / highest reward cards in the game. This company is blocked from exiting in Series A, B, or C.

But if there is an exit after, there is a 2-12X increase in the exit multiple (rolling two dice).

This company is purposefully designed to be more expensive ($9M vs $1M of some of the other cards). But there is almost no reason not to invest since this one company would probably win you the game. It's an example of “power law seeking” behavior that should be every player's strategy.

Other concepts

Besides time and the Power Law, there are other VC concepts taught through Swagger:

- Dry Powder - The concept of reserving cash to invest in companies that take off and raise more and more capital. To make it extra harsh, in the game any startup that cannot raise automatically goes bankrupt.

- Valuation - Valuation is represented in the game as the “price” you pay to invest in the company. Lower valuations at the early stages saves dry powder for later investment. But, as long as a company exits, the later stage valuations hardly matter.

- Competition - VCs obviously compete for dealflow, but from a macro level the ability of a GP to raise another fund is tied to their performance. Though Swagger.vc only takes place during the life of one fund (for now), it's realistic that all fund managers are competing for future LP dollars.

- Value add - I recently added the concept of special Action cards that allow players to add value through their own special abilities. Eg the Self-Declared Visionary card allows a player to see what will happen to the industry in the future. Realistic or not, these cards allow players to test out a fund strategy based on value add (versus an industry focus). Plus they're fun.

Wrap up

There is huge potential to use games to teach business concepts. It's a faster way to learn and much more fun. Unlike a book or a lecture, it also avoids one of the worst aspects of founder education: the illusion of certainty.

Because being certain makes you appear smarter, almost all founder education is of the form “I successfully did X and here's how you need to do it.”

In contrast, games include randomness and unpredictability, especially when other players are involved.

You need to learn the rules but then be creative.